A perk for the prosperous, or a driver of density? We unpick the principles of adaptable living and high-density home design, examining and comparing the differences across the UK and Asia’s residential sectors.

In the throes of ‘crisis’; the current UK housing situation

In the UK, a historically low delivery of homes over the past 50 years coupled with a comparatively high growth in population has led to the much publicised ‘housing crisis’, a struggle to meet ambitious homebuilding targets, puncture property inflation and make houses more affordable for future generations.

Numerous bodies have insisted that if the UK is to even come close to meeting its projected housebuilding figures, it must embrace modern methods of construction.

Another less mainstream viewpoint – but still one shared by various experts and think tanks – is that as a society, perhaps we should lower our expectations and needs with regards to the actual physical space required of our homes.

Is modesty the new modernity?

While there is an evident need to encourage higher density living arrangements if we are to curb the rapid ascension of property prices and make more of Generation Y into first-time buyers, there is a delicate balance to be maintained.

Micro-living arrangements could be a step in the right direction, but the inherent challenge of this principle is that, when pushed to the extreme, continual pursuit of it will eventually present a trade-off in terms of individual comfort and quality of life.

Smaller spaces might be viable for those living in the buzz of a capital city or within walking distance of their workplace and other vital amenities, but with typical urban residents migrating outwards later in life, can this ever be an effective long-term solution? What will happen when those same residents wish to raise a family?

Micro-living solutions might also present quickly diminishing returns with regards to their affordability benefits, with the potential for smaller homes and higher densities pushing up the cost of land and, as a result, purchase prices.

Despite the need for affordability, houses still need to be desirable as well. Focusing on a more uniform, volumetric approach to building houses driven by modern methods of construction may help the UK close in on its targets, but will it do so at the cost of character, and attractive design?

Finding the sweet spot

The challenge then, is to concurrently fit as much function and comfort in as small a space as possible and to build houses in such a way that we can deliver on both volume and variety.

In order for urban residential developments to be both effective and sustainable in accommodating future urban population growth, there is a need for more than just infrastructure built with density in mind.

We must strive not just for space economy, but for design innovations that make spaces work harder across a broader spread of functions – in other words, we must strive for adaptability.

I believe that, if developed in the correct way, innovations at the forefront of adaptable living could serve to present a feasible middle ground of housing that can be produced at large scale without compromising on affordability, spaciousness, aesthetic appeal or individuality.

The Victorian terrace: Britain’s most iconic high-density housing solution

In the 1800s, birth of new industrial and manufacturing cities had ushered in an era of unprecedented demographic change and rapid population growth, bringing with it a boom in housebuilding.

The UK began to build for density, crafting rows and rows of now iconic housing typologies on terraced streets.

Brick and stone being the most abundant and readily available construction materials at the time resulted in these houses becoming big, heavy structures – they were not high rise, but they were dense.

Intergenerational wealth was low, so families would live together for long periods of time in order to remain financially secure, and with the average parents bearing around six children, these homes needed to be capable of maximising the functionality of the available space.

Zig-zagging doors enabled rooms to be opened up and rearranged, while convertible furniture made storage and sleeping spaces interchangeable, and even allowed homeowners to scale their living arrangement up or down to entertain and accommodate differing numbers of guests.

Victorian homes are also revered to this day for their remarkable ability to be built upon. Much to the awe of modern DIY enthusiasts, their durability allows for growth, extension and expansion that would make a modern estate house crumble.

But while touches like zig-zagging doors and stackable furniture did help spaces work harder, these homes were still ultimately built around a desire to compartmentalise – to fulfill Britain’s deep-rooted cultural need for privacy and security, with isolated, separate rooms serving isolated, separate functions.

Fast forward to now, and several periods of social mobility and increasing wealth have made this culture of compartmentalising all the more apparent. Density has waned drastically while the yardstick of what constitutes a respectable plot of private land has grown more self-serving and ambitious.

So how have other cultures approached the notion of living space in the past? Perhaps there is something to be learned from how Asian countries have historically favoured high-density housing and adaptable interiors.

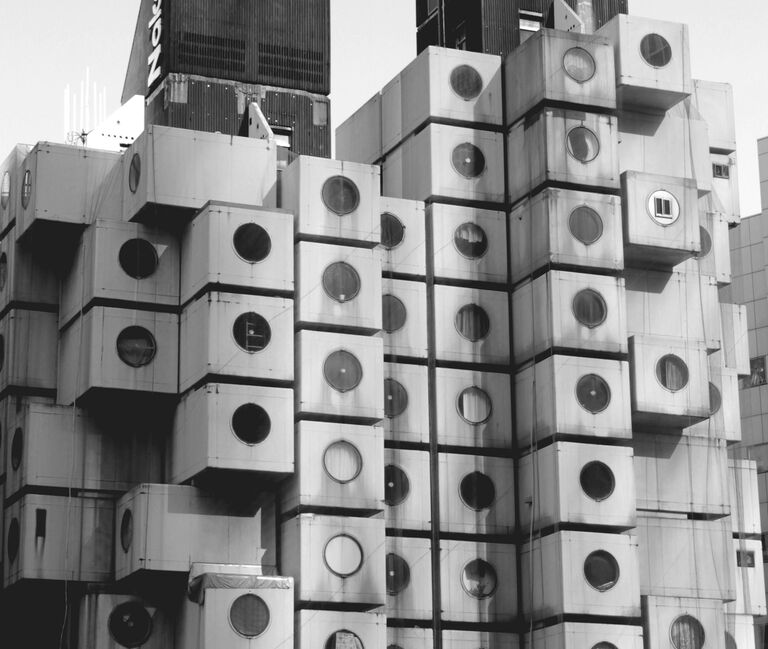

Asia’s history of high density

Micro living is nothing new. In fact, it has long been the norm for many of Asia’s thriving cities, centuries before the inception of the Victorian terrace.

Asia embraced a more modern approach before the West invented what they thought to be modernism.

As far back as the late 12th century, Asian homes have had flexible spaces, with the architecture of the Japanese Kamakura period centring around fluid movement and compact storage innovations.

Most furniture was made of materials that could be wrapped up and put away, while the buildings comprised timber structures fitted with large shōjis, the immediately recognisable sliding doors capable of merging or dividing the spaces of multiple rooms as appropriate.

A room could be opened up during the day to accommodate various other occupants and activities, before being compacted in the evening down to the size of a tatami mattress and bedside table.

As well as being able to physically add and subtract space with ease, their paper and bamboo makeup also helped to create the illusion of more space by maximising the intake of natural light.

One could easily argue that, historically, Asian cities have had to embrace fluidity and space economy, often due to being based in small, flat settlements surrounded by mountains or large bodies of water. The modest and compact pang uk ‘stilt houses’ built in the fishing town of Tai O and the ultra-methodically built walled villages of Hong Kong in the 16th century are clear examples of the latter.

In Hong Kong, the solution to population density has long been an approach similar to that of the Victorian terrace, only built up rather than along – which allows them to be built on the larger scale befitting to their denser urban population.

Innovations from Asia’s luxury residential market

So how are these principles of more fluid spaces like those in Japan, or more compact, tall and thin spaces like those of Hong Kong being expanded upon in the present day? And can observing them be of assistance to us in the UK, as our government scrambles to regain housebuilding momentum?

Interestingly, some of the best ways of increasing affordability within the UK housing market could in fact lie within Asia’s luxury residential market.

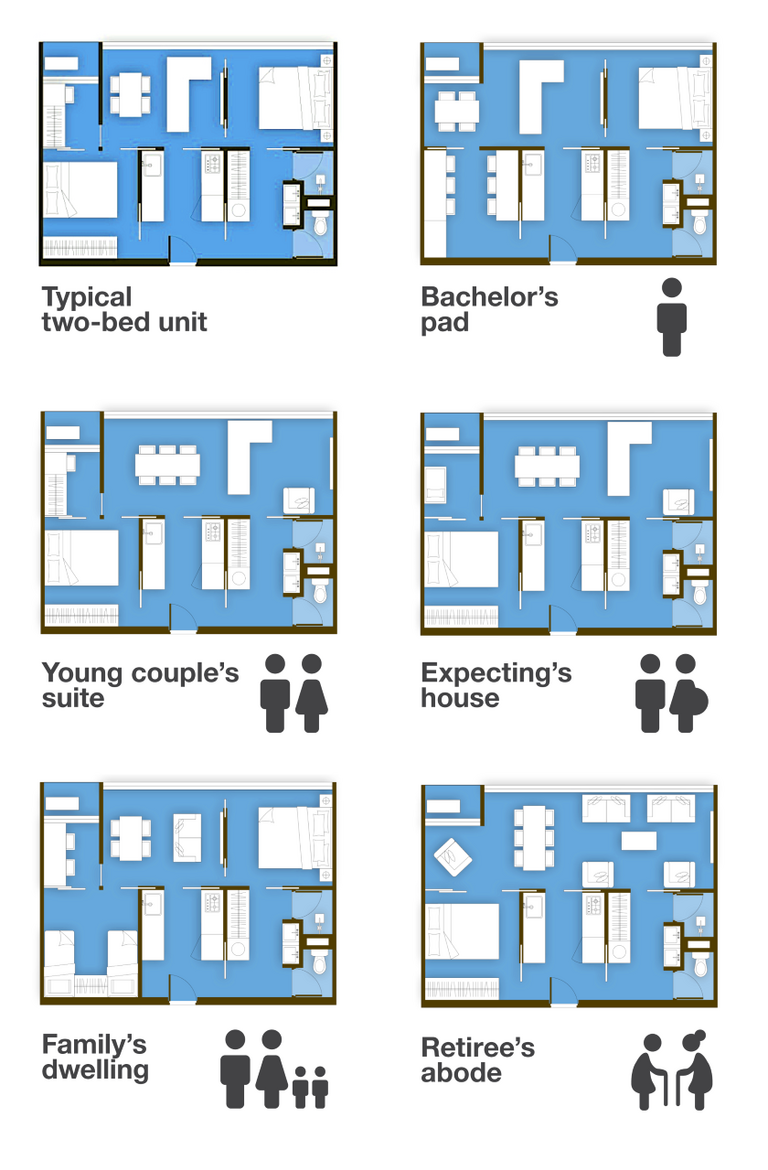

A growing idea among condominiums and luxury apartments in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia and beyond is that of not simply selling an apartment to an occupant, but instead selling them an adaptable unit, the value of which far transcends its measurements in square metres.

One such unit we have worked on is intelligently designed to adapt and grow parallel to one’s life trajectory, with limitless potential for tailored configuration and utilisation of space.

Introducing the unit that grows with you

This residential apartment unit comprises a dry wall system that is subject to limitless modification, as well as a number of sliding doors which, like the shōjis of 12th century Japan, allow for the separation and or opening of spaces on the fly.

The dry walls can then be adapted and moved around as shown in these images – as you can see, here we have presented examples on the basis of the occupant’s changing from those of a single young professional, to that of a young couple, new parents, then retirees.

These adaptable features are also further buttressed by smart, flexible modern furnishings which are innovated with space-saving in mind.

In the images below, see how sliding reflective doors can close or open up space without a feeling of being restricted or closed off, while the breakfast bar can be neatly extended or tucked away as appropriate.

Overall, this unit not only provides value in the sense that it allows someone to purchase a one-bedroom unit for a one-bedroom price before self-converting it into something larger, but it also gives residents the autonomy to define their own areas of work, rest and play.

It allows someone to tailor their unit to reflect their own individuality and lifestyle – to shape their space around their own unique mix of needs, interests, habits and hobbies.

By putting the ability to define one’s living space and its purpose directly in the hands of the occupant, perhaps we can create variety in uniformity.

Why we should build on a chassis, not reinvent the wheel

I am of the opinion that the UK, and more of the west in general, could return to building high density streets. We can look to build terraces that grow up like the walled villages of Hong Kong, and along like the Victorian terrace, with fluid spaces reminiscent of the Kamakura period.

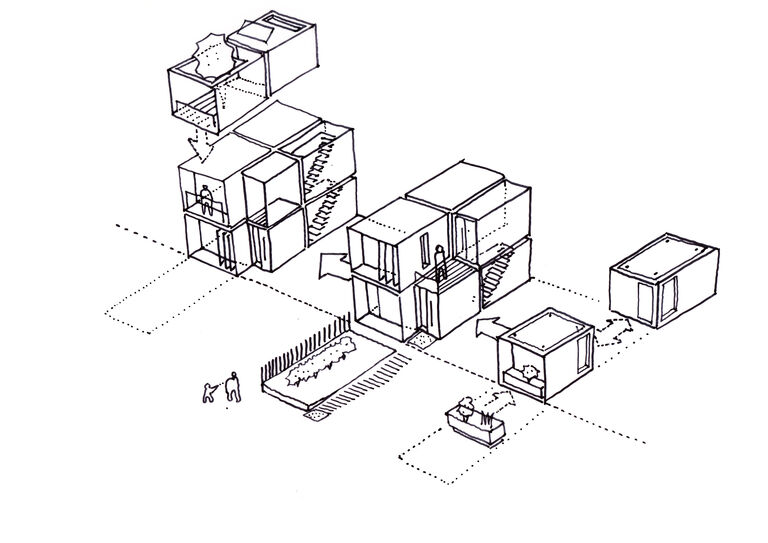

I often wonder whether the middle ground or sweet spot that combines all the design objectives detailed above – volumetric construction, comfort, functionality, sustainability, a customisable home space that one can call their own – can be achieved by taking the concept of the “adaptable unit” at the forefront of Asian luxury and expanding its scope for configuration.

Why stop at having a room that grows with you, when we could extend this principle to entire homes and communities. Mulling over this idea, I found an oddly familiar sentence echoing around my head: “start small, add to it, rearrange it, and take it with you when you move”.

I soon remembered that this was the strapline for the ingenious shelving units designed by leading design thinker Dieter Rams. These worked on the principle of having a basic foundation that could be invested in, enhanced, added to and customised over time in line with the changing lifestyle needs of the owner.

In his “good design principles”, Rams stated that good design is innovative, useful, unobtrusive, long-lasting, environmentally friendly, and finally, that “good design is as little design as possible”.

The Victorians weren’t reinventing the wheel in order to leave their mark on British culture, they simply worked from a pattern book – the passage of time seems to be ultimately what rendered them timeless jewels in the crown of our cultural identity.

Maybe then, the way we can move forward, and work in a way that allows us to build up as well as out as people’s lives and communities change and scale up and down is by looking at housing units like these shelving units – treating a home like a chassis that can have additions and enhancements bolted onto it and extended, which we can build up and out as people’s lives and communities grow, then scale them back down and move them when spatial needs decrease, or if the homeowner wishes to move or sell the property on.

Right now, we need to fine tune our vehicle for progress, and my view is that choosing to build upon the chassis is better than continually reinventing the wheel.