Environmental design for me is about combining the technological know-how of today, with the rich vein of knowledge that exists within the history of architecture – to re-examine the wisdom in the story that we are now a part of writing.

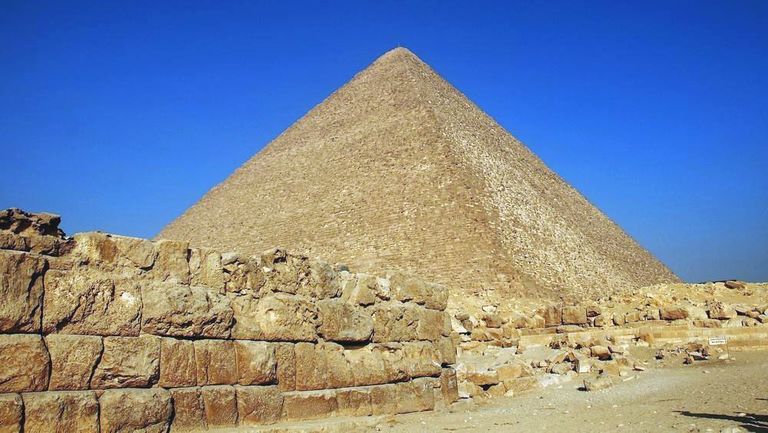

Construction has not always been like this. Before oil (and coal), the history of architecture was written by energy sources much less abundant and much more uneconomical; the result was buildings that were almost always re-used in some form or another – the initial energy that had gone into material collection and assembly was garnered back wherever possible.